How to become the company MVP

A discussion on company MVPs, heroes as single points of failure and how to create a limitless organization

Featured on:

Business leaders love to bring up sports teams as an analogy. It’s pretty understandable. Sport is almost always a team endeavour, whether it’s the team you see playing or all the support staff in the wings. Similarly, no one succeeds in business without a team. Sports has other aspects that we look to in business: the idea of an “enemy”, tactical and strategic planning, and the requirement for flawless execution. Such comparisons naturally have caveats; life is rarely 80-odd games capped by an annual championship run. But let’s lean a bit more into the analogy and check out the role of an individual in a team sport and in business.

In sport, the greatest MVP—most valuable player—of all time for most people of my generation will be Michael Jordan of the Chicago Bulls. His dominance as a player and personality at that specific point in time in the media is legendary. What is brought up more often than not in talking about Jordan is that he and the Bulls are a very good example of needing the talent, the right coach, and the right organization. Without the right coaching staff and playing as a team, Jordan would never have become the winner that he did as was proven so often early in his craeer. Business “MVPs” whom we “lionize” in the media include Steve Jobs, Sheryl Sandberg, and Bill Gates, to name a few. The way we talk about tech leaders is not unlike historical personalities around whom events seemed to spiral.

The Great “Person” Theory

In the 19th century, it was popular to assert that history swirled around heroes. A popular thought experiment posits: If you could prevent Hitler from being born, would World War Two have happened? The Great Man Theory, as it’s called, would answer that yes, he was the force of personality around which that war happened. Nowadays we would argue that the list of variables is so immense that likely a world war at that time would have happened regardless of the birth of Hitler.

Absolutely, the combatants might have had different outcomes, the atrocities might have been less or more severe, but the situational context provides ample argument that the theory cannot simply be true. And yet, in business, as in sport, we still hang dearly in the wider imagination to the idea that success can only happen through single individuals like Elon Musk.

Seeking heroes

We want the idea of a hero to be true. We are brought up on a steady diet of comic books and childhood fantasies, from Marvel to Harry Potter, where a small collection of the smartest and most powerful will save the day. With such a loud cultural presence, it’s no wonder that we model ourselves after such constructs. Not only do we picture ourselves and strive to be such heroic figures, but we also manifest the wish to have heroes in our reality. We seek heroes in our schools, workplaces, and even in our families. Part of this is that we seek to create a connection with those we deem worthy and look up to.

In my opinion, this need to seek and be heroic can lead to all sorts of group dysfunctions. My job as a business leader is to weed out so-called “heroes” and make every person an MVP. Despite short-term success, a company made of a couple of “heroes” around whom everything revolves is a company that will fail, and fail hard.

Heroes as single points of failure

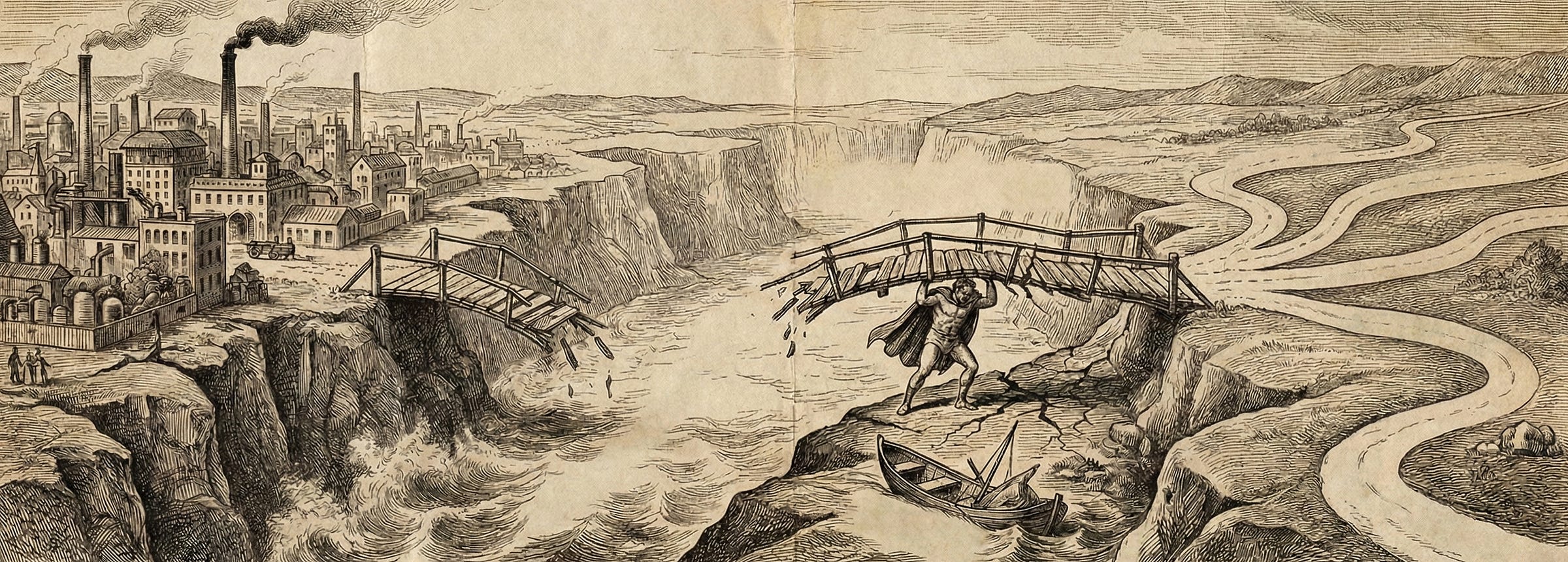

To put it bluntly, a “hero” is a single point of failure. In systems design, you want to build flows which do not come to a point. For example, you don’t want the majority of a country’s power supply to go through a single remote switching station. I witnessed the outcomes of exactly that in Chile earlier this year. When I put it like this, I am sure everyone laughs and says, “Yes, that’s pretty stupid,” but we all do these things all the time.

Programmers can rely on a single database out of simplicity, hospitals can rely on one single source of power, and individuals can live from paycheck to paycheck with zero buffer. A disruption in any of these can cause a chain of failures, a lot of which we witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic. We all create single points of failure due to the expectation that the patterns we observe will continue to behave without change.

While the examples I cited above reflect systems design or behavioural patterns, all of these do apply to business and organization design. We all know the person in the company who knows the most about some arcane piece of technology like the speaker system or who works hardest on a project. These are all single points of failure.

The supposed “MVPs”

Over the years, I’ve had any number of people tell me that their goal is to be the person everyone comes to. This, they say, gives job security. This, they say, makes them the MVP of their team and company. Frankly, that’s total bullcrap. Instead of being an MVP, they are modeling themselves to be a danger to the organization. I’ll outline three archetypes of such behaviour:

The Knowledge Base: This is the person who wants to be the central point of contact. You can immediately see that while this person thinks they are the MVP, they are a liability to the company when they get sick or go on holiday. This usually starts out as something very positive in the mind of the individual, with a great dopamine rush when you are wanted. Over time, it degrades to a continual mental and emotional drain as the company or work scales, and eventually, they burn out. You can spot these people when you see a single person doing an important function. As a leader, I want to build redundancy, which is not the same as saying hiring more people. Instead, I need to facilitate knowledge and experience transfer such that it is decentralized and easily available.

The Martyr: I have played this role many times. This is the individual who does heroic work and rides to the rescue. They ask for no help and may even actively push back with comments such as “I can do it faster.” These can be your 10x coders, the ones who don’t sleep for days and get things done. Don’t get me wrong, individuals who step up are extremely valuable, and these individuals are often creative and can move mountains. You might not even understand their vision until whatever they are doing is done. They are absolutely MVPs, with a big “BUT.” When it happens too often without involving others, then lots of dysfunction can arise. In such situations, they shut down diversity of thought and can stop others from even trying. “If Jane can save us once, then she can save us again.” We fall into the trap of idolization and hero worship.

The Steve Jobs Wannabe: This archetype is the manager or leader who must have the last word and the final decision. They want to be seen as the decisive hero who “drove the success.” Sometimes, they can be the leader who takes the credit for their team’s work and ideas. People can do this without thinking; it’s hardly ever malicious, but the outcome is dysfunctionality. The team slowly becomes disempowered—”If Joe always makes the decisions then what do I care?” A team might even start to think the reason is that this person has more information, and it might have the inverse effect of stopping them from bringing new information. Usually, this results in shallow decisions, and worse, great people will leave as they never get acknowledged for being an MVP.

How to spot an MVP

Despite my distaste for single points of failure, I too am a product of this culture. I do believe heroes are important and there really are MVPs in an organization. However, if you want to create a limitless organization, the trick is to make sure everyone has a chance to become a hero and that when they show some aspect of being a situational hero or MVP that they or you do some of the following:

Work in teams to disseminate information and experience so they build resilience. Have them become teachers rather than hoarders of knowledge.

When a person goes out to “save the day”, which shows loyalty, ability, and often caring, make sure that there is a team and a plan. When you give kudos, give it to the wider players rather than to a single person.

When a manager or a leader constantly says “I drove...”, “I am the reason for...” it could be that the team reporting to this person might not be being elevated. Make sure you have conversations to unblock such problems before they become worse.

We started talking about how business leaders use sports as an analogy. Let me finish by describing my favourite MVP in sports when I was growing up obsessed with the NBA. My MVP was never Michael Jordan. He was for sure the finisher with agility and artistry second to none. The MVP and the person I wanted to be were his teammates with the most assists, the people who fed the ball to MJ so beautifully, the guy who grabbed the boards to get a second chance.

I think the true MVPs of an organization are those that set others up for success, teach, and quiet the noise so others can deliver. They are the people asking the questions which lead to greater diversity in thought. I do acknowledge that I am a doer and a force of nature when I want to be, a martyr and then some; the MVP I have always sought to be is the great supporter. I am hoping that my positive tally is growing faster than the negative. And here I leave you with the final thought which is a text a friend sent this past week: “When your company is starving, the hero is not the one who goes and gets the fish, it’s the one who teaches everyone to fish.”

Leadership Health Check: Are You Building a Team or a Kingdom?

Use this checklist to evaluate if you are fostering true MVPs or creating dangerous dependencies.

Identifying the “Knowledge Base”

[ ] The Bus Factor: If this person (or you) were hit by a bus tomorrow, would critical operations stall?

[ ] The Vacation Test: Do you feel guilty or anxious about taking a vacation because “things will fall apart”?

[ ] The Hoarding Check: Are there tasks that only one person knows how to execute?

[ ] Action: If you checked any of the above, immediately schedule a “shadowing” session where this person teaches a colleague how to perform a critical task.

Identifying the “Martyr”

[ ] The Hours Log: Is there someone consistently working late nights or weekends while others leave on time?

[ ] The Help Refusal: Does this person frequently say, “It’s faster if I just do it myself” when offered help?

[ ] The Hero Narrative: Do you rely on the same person to “save the day” at the last minute for every deadline?

[ ] Action: Enforce a “no-hero” rule for the next project. Assign the “Martyr” a role that is purely advisory or educational, forcing others to do the execution.

Identifying the “Steve Jobs Wannabe”

[ ] The Bottleneck: Are decisions waiting in a queue for one person’s final sign-off?

[ ] The Silence: In meetings, does the team wait for the leader to speak before offering their own opinions?

[ ] The Credit: When a project succeeds, does the leader say “I” more than “We”?

[ ] Action: Implement a “speak last” policy. The leader must listen to everyone else’s input before sharing their own opinion to avoid anchoring the group.

Building True MVPs (The “Assist” Mindset)

[ ] Resilience: Have we documented our processes so that information is decentralized?[ ] Elevation: Did I acknowledge the person who helped the scorer today, not just the scorer?

[ ] Teaching: Is “teaching others” a metric in our performance reviews?