Fiction in the age of AI

When I started working on my fiction after decades of neglect, I wondered, "Why bother? AIs will get so good people wouldn't want to read my stories." Let's answer that question

“AI has killed/will kill _ why bother doing it?!” Replace the blank with anything you wish at this point. The hype cycle is fit to bursting at the seams.

When I started working on my fiction after decades of neglect, a small part of me began to wonder, “Why bother? AIs will get so good people wouldn’t want to read my stories.” It wasn’t just me wondering; people started outright saying that to me.

Why bother?

Today’s generative AI models such as ChatGPT, Claude, and Geminihave sucked up much of the world’s literature. If you can imagine a giant gelatinous cube running roughshod over libraries, that would be a good image to have. Unfortunately, I do suspect that in their haste and eagerness, perhaps in willful ignorance as well, these models have sucked in many copyrighted works. As such, if you want a new Harry Potter novel written in the style of Rebecca Yarros, you are pretty much one prompt away. For a less illegal reference, you could probably also do a passable Sherlock Holmes story with a prompt such as “The case of the disappearing poop emoji.”

There’s no surprise that people get upset about authors publishing works clearly produced using such technology. Depending on how you view the legality of what has been used to train these systems, such “authors” are at best “curators” or “prompt artists” and at worst “plagiarists” and “criminals”.

Where the world end’s up will likely be somewhere in between.

In some ways, the world of writing in totality will go the same way as photography. When very few people had access to a camera, every photographer had a higher chance of being celebrated and having a meaningful profession. When everyone in the world can create photographs, to have a profession means you have to rise to the top and your photographs must really tell stories that matter. If everyone can write a novel without the hard work, then the core of the novel, its creativity, its cultural resonance, and its ability to drive new ways of thinking will matter even more. For me this is where our current generation of AIs fail.

These systems cannot do true storytelling; unless they actually achieve true physical and emotional sentience, they will never do so. Our species has conquered the planet and beyond through our abilities to tell stories. We create mental models of everything around us, our lives, our environment, our people. We use those models to construct vivid possibilities into which we pour effort and creativity. We use the mediums at our disposal, whether that be clay tablets, architecture, papyrus, or computers, to convey those stories to drive each other. The better the story, the more likely to survive, the more likely to drive us to action.

ChatGPT may create a story that looks legitimate, but it is still a statistical amalgamation of words based on precedent. It cannot yet understand the horror and the physical pain as you lose a loved one. It cannot change its role in society as you would from having a home to being homeless. It cannot feel the approaching end as your dementia steals your memories into wispy echoes. To describe any of that, it is using past words and past ideas to construct a mere possibility, and that possibility is not unique to you and the story you wish to tell.

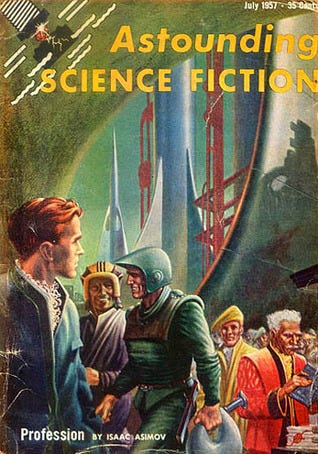

I am reminded of a story by Isaac Asimov called “Profession.” In this short story, a young man fails to be part of normal society where people are educated by beaming data into their minds. This man remains “uneducated,” a failure in this society. In the end, the curtain pulls back and it is actually these “uneducated,” rebellious thinkers who are creating the new works to teach those who are being “educated.”

You can take this story in so many ways. The AI models we have today can certainly be seen as a crucible of knowledge. While we can use the technology responsibly, true creation is still up to those who are outside the model, those who are—to sadly quote an Apple advert—the rebels, the artists, the thinkers, and the rule-breakers. As it has always been.

There will likely be a future for “prompt artists” who will mould the technology and medium of GenAI—however long that period may last—towards some form of art. AI, in its current form, is far from the end of fiction.

What I am most concerned about isn’t whether the story is AI generated, but where our society is going when it comes to consuming stories. If everyone can be a writer and everyone can be a publisher, then what does it mean to be a reader? Even as I record this podcast, I know that the world is drowning in writing. More people than ever are reading: we spend most of the day in front of screens reading volumes of text, Slack messages, wiki articles, transcripts, documents, and more. Now you crave the story being read to you, as I am doing right now. You crave the story being shown to you on screens or on stage. I worry that stories based on the written word are slowly being erased from our cultures. You might say, “Does it matter?” A story, after all, is a story.

For me, the written word is a very different beast from what you see or hear. These are stories that you can mull in your mind; stories which you can scan your eyes backwards and forwards. There are word tricks you can use that shape your fascination and curiosity. You can break rules of language that you cannot in spoken or visual mediums. It is true that we write for people to read our stories aloud.

Take for example the following two lines from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit:

“The yells and yammering, croaking, jibbering and jabbering; howls, growls and curses; shrieking and skriking, that followed were beyond description. Several hundred wild cats and wolves being roasted slowly alive together would not have compared with it.”

Compare that to any scene you can watch. What you would see is a poor reflection. You can hear me reading that in the podcast. There you will hear my voice, my intonations, my own biases. Reading that with your own internal voice, at least for me, makes me want to plug my ears at the din and horror that Bilbo Baggins was witnessing.

So why bother?

People, like me, are compelled to write and tell stories. These are the stories that help us create the worlds of tomorrow and understand the humanity of today. I can only hope that you read them in the form in which they were created. Yes, AI might be able to create an upside for writing, for example as a tool for brainstorming, researching or even getting past writers block. In the hands of a careful prompt artist, such writing even meet some measure of success. However, when it comes to our human existence, locked in our little heads, carried by our frail and limited physical frames—these new stories we as humans create based on that existence—and hopefully stories you will one day read—these are the stories that will carry the seeds of our future, our past, our hopes, our fears, and the beauty of sheer imperfection.